Lead levels in drinking water were unsafe in 1 out of every 4 California child care centres that complied with the first state testing requirement.

California child care centres were required to test their drinking water for possible lead contamination for the first time in state history. According to data recently released by state regulators, approximately 25% of those that reported results had levels of lead that were unsafe.

Almost 1,700 of the approximately 6,900 centres whose findings have been made public had lead levels higher than the state-permitted threshold of 5 parts per billion (ppb) for child care facilities. 13 of them, including four in the Bay Area, had lead concentrations greater than 500 ppb.

Out of all the child care centres in the state, La Petite Academy in San Diego had the highest lead levels detected, at 11,300 parts per billion. That is about ten times more than what California permits and more than 2,200 times greater than some of the highest levels found during the disastrous water crisis in Flint, Michigan, almost ten years ago.

Since then, the facility has removed the two drinking fountains with the highest lead readings, and subsequent retesting of the remaining water sources revealed that they are safe, according to centre spokesperson Joanna Cline.

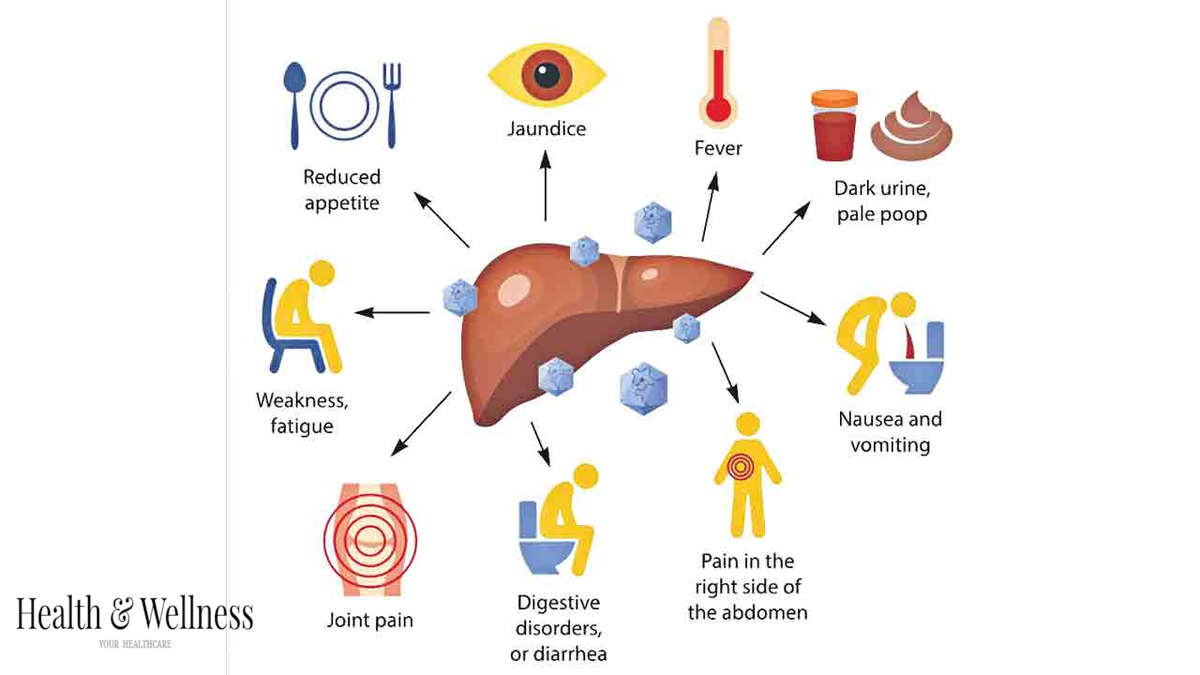

The findings suggest that the young children at those centres have been consuming lead-contaminated water for years, which is concerning because, according to Susan Little, a senior advocate with the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, which examined the test results, children’s bodies are capable of absorbing up to five times as much lead as adults.

Little told KQED, “What’s so tragic about this is that this testing is an indicator of what could have been going on for decades in the drinking water in these centres throughout the state, in addition to being an indication of existing problems.”

Lead is a poisonous element that is present in the environment, can get into drinking water through corroded pipes, and has been shown to be harmful to children’s developing brains and nervous systems in high concentrations. Lead exposure, even at low concentrations, has been connected to behavioural and cognitive issues as well as developmental abnormalities.

Due to these factors, the American Academy of Paediatrics advised in 2016 that lead levels in school drinking water not go above 1 ppb.

The state law, AB 2370, which was passed in 2018 and mandated that all licenced child care centres housed in buildings built before 2010 test every tap for lead poisoning by January of this year and then sample the water every five years, is what prompted EWG to conduct this study.

As per the rule, any facility having water above the 5 parts per billion standard would have to get rid of lead as soon as possible.

Child care centres are held to greater standards than elementary, middle, and high schools, which are exempt from testing every tap, replacing fixtures, and notifying parents until lead levels are above 15 parts per billion.

This year, Assemblymember Chris Holden—the author of AB 2370—introduced a bill requiring schools to adhere to the same regulations as child care facilities.

Holden stated in a statement, “We can protect children from the toxic effects of lead by aligning childcare and school lead testing standards.”

There was a two-year period during which child care facilities might have lead contamination in their drinking water tested. However, according to EWG’s study, hundreds have still not filed data months after the deadline.

Little stated that when additional test results are received, she anticipates an increase in the number of sites with hazardous lead exposure.

“It seems like this is just the beginning,” she remarked, pointing out that lead testing is not even necessary for licenced family child care homes in California, which outnumber child care centres.

Little suggests that parents who enrol their kids in family day care centres urge the operators to upgrade their faucets and add lead-free filters.

When a parent sends their child to a centre, they have the option to check the lead-level results (PDF) on EWG’s database and request that the facility test their water if the results are not available there.

Little advises parents to inquire about the providers’ steps taken to reduce lead levels in the water if it is discovered that the centre has a hazardous level of the metal.

The lead levels at ABC Preschool in San Francisco, which had the fourth-highest lead levels in the study, were caused by an outdoor washbasin that had been off for years, according to Kumiko Inui, the director of the school. However, she added that the school has a filter and that other fixtures at the multilingual preschool for Japanese and English were below 5 ppb.

She remarked, “I’m disappointed to get this kind of attention.”

According to Jessica Griswold, principal of Martinez’s St. Catherine of Siena, which came in fifth place in the statewide survey, water from a sink in the director’s office that had also been inactive for a number of years contained significant levels of lead. She explained that rather than getting their drinking water from fountains these days, pupils use dispensers as a precaution.

A representative for Kidango Linda Vista in San José, which had the eleventh-highest lead levels, stated that the facility retested the water and replaced faulty supply lines and fixtures.

Mario Fierro-Hernandez, the spokesperson, stated in a statement that “we are pleased to report that each classroom at Linda Vista now has alternate fixtures that dispense water containing zero lead particles.”

The troublesome fixture, according to Tiffany Teele, director of the Bunker Hill Parents Participation Nursery School in San Mateo, which had the 13th-highest lead level, was an outdoor tap used only for hand washing. Since then, she claimed, the school has changed the tap, retested the water and been cleared.