Following investigations, Kaiser relaxes its restrictions on postpartum depression care.

After numerous attempts to seek treatment, Miriam McDonald felt like an empty shell a year after the birth of her son Nico. At that point, she “came out” as having severe postpartum depression, a decision she now says was well worth it.

McDonald fought Kaiser Permanente, her insurer and healthcare provider, for months when they refused to provide her access to brexanolone, the only drug for postpartum depression that has received FDA approval.

However, since she revealed the specifics of her ordeal in a 2021 KQED investigation, Kaiser has revised its coverage guidelines twice, per recently obtained internal documents obtained by KQED. Additionally, federal regulators have opened an ongoing investigation into the insurer, citing KQED’s reporting.

After learning of Kaiser’s policy changes, McDonald remarked, “This will prevent other women from having to go through a year of depression to find something that works.” “After having a child, no woman should have to suffer like I did. The policy was completely unjust. I was in the afterlife.

In 2019, McDonald began to feel suicidal thoughts and other symptoms of postpartum depression. According to Kaiser’s published criteria, patients had to attempt and fail four drugs in addition to electroconvulsive treatment before they could receive brexanolone. However, experts claimed that since the medication was only authorised for use up to six months after giving birth, this amounted to a general rejection for all Kaiser patients and might have violated both federal and state laws.

Kaiser revised its guidelines a month after KQED published its investigation, advising women to try only one medication before being eligible for brexanolone. If the trial could not be finished within the six-month period, women could skip it and go directly to brexanolone.

Subsequently, a federal probe

However, Kaiser’s problems didn’t end there. Based on documents that KQED examined, the federal Department of Labour had opened an investigation against the insurer by late 2022. Investigators spoke with other patients and called McDonald to learn about their difficulty getting postpartum mental health services, such as brexanolone.

Kaiser amended their brexanolone guidelines again a few months later, in March 2023, eliminating all instructions to fail first. All patients have to do is say no to a trial of an alternative drug.

As a matter of policy, the Department of Labour “will not confirm or deny the existence of an ongoing investigation,” but it also said that it might sue a private insurance and make it alter its policies if they break federal law. This was stated in an email to KQED. It can also compel insurers to pay for care or return patients’ out-of-pocket expenses for treatments that the department determines were wrongfully refused.

Postpartum therapies: a new era

By focusing on hormone function rather than the brain’s serotonin system, as standard antidepressants do, brexanolone was introduced to the market in 2019 with the goal of revolutionising the treatment of postpartum depression. Women with moderate to severe depression reported quick alleviation from the three-day treatment in early trials. Brexanolone, however, comes at a high cost—$34,000 per treatment—and needs to be administered intravenously while a patient is in the hospital, where they may be closely watched for adverse effects like fainting.

For new moms seeking therapy, the cost and the difficulty in locating a hospital with the necessary accreditation to give the medication proved to be deterrents. Women had to be referred by Kaiser to one of just three other accredited hospitals in California because the hospital lacked its own certification until recently.

The FDA authorised zuranolone, a new, more easily obtainable pill form, in August. It is to be taken once daily at home for a period of 14 days. The manufacturer of both medications, Sage Therapeutics, set the price of zuranolone at $15,900 in November.

Since then, a research using data from Policy Reporter, a website that records insurance policies, shows that less than 1% of health plans have set criteria for when they will cover it. Advocates, attorneys, and regulators are keeping a close eye on how insurance companies will draft guidelines for the new medication.

Meiram Bendat, a lawyer and certified psychotherapist who helps patients, said, “We’ll have to see if insurers cover this drug and what fail-first requirements they put in.”

The legislative landscape surrounding mental health treatment is changing at the same time that these new rules are being drafted. In order to ensure that insurers pay mental treatments on par with physical treatments, the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act is being enforced more strictly by the federal Department of Labour.

Insurance companies are subject to new, more stringent reporting and auditing regulations that go into effect this summer. These measures aim to improve patient access to mental health care and, according to campaigners, may force insurers to create more cautious plans in the first place.

As of 2021, insurers in California will also need to ensure that their coverage policies are in line with widely acknowledged standards of treatment by adhering to an even more comprehensive state mental health parity statute. The law’s much anticipated regulations should be published this spring.

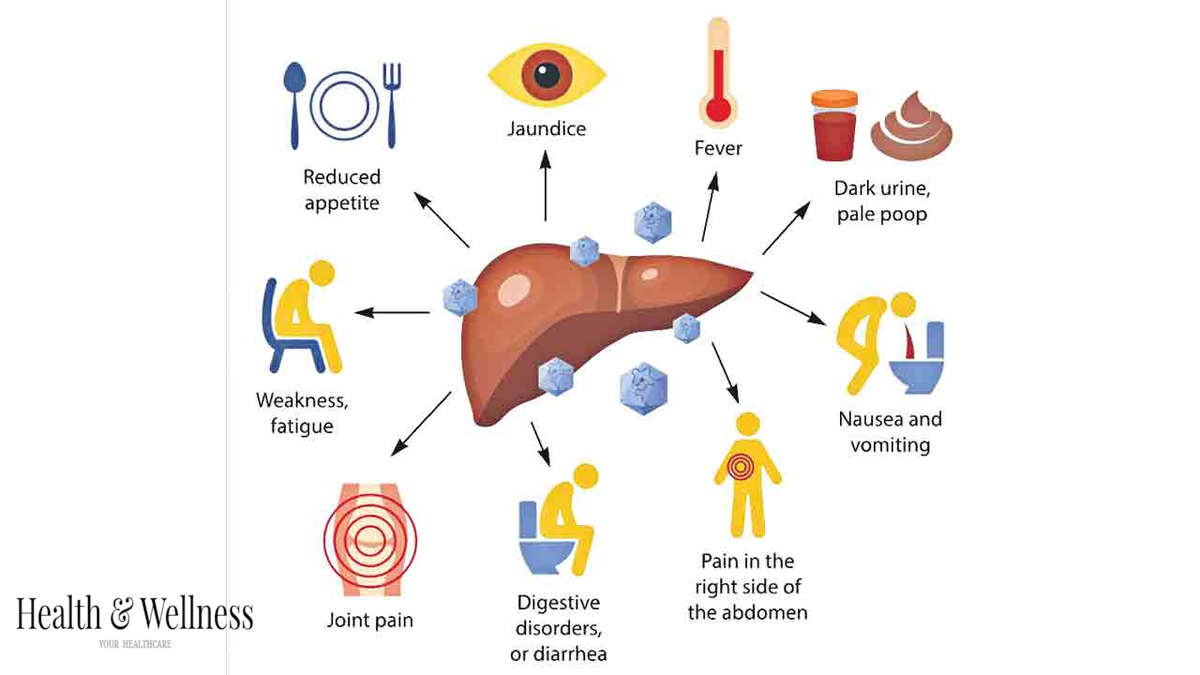

Numerous perinatal psychiatrists told KQED that it is critical to treat postpartum depression as soon as possible in order to prevent adverse effects, such as the baby developing cognitive and social issues, the husband or partner experiencing anxiety or depression, or the mother dying by suicide, which is responsible for up to 20% of maternal deaths.

This could be the rationale behind Kaiser’s hasty 2021 revision of its brexanolone standards, according to Burkhard, an advocate who had previously worked for an insurance business. However, it’s unclear what standards Kaiser will have for the novel medication zuranolone.

“The evidence-based, expert review process that we use for all medications will also be applied to zuranolone,” Kaiser stated.

According to McDonald, women will now have more options for care in terms of both policy and practice, including quicker-acting therapies that they can get right away. She wants them to be free to select the best course of treatment rather than being compelled to ride a never-ending drug roller coaster like she was.